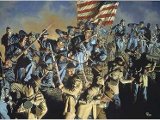

Surrender at Appomattox Courthouse

Significance of the Surrender at Appomattox Courthouse

The surrender of General Robert E. Lee to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, on April 9, 1865, is traditionally viewed as the end of the American Civil War although scattered fighting between the Confederate and Union forces continued for several months. However, Lee’s surrender followed by the surrender of Joseph E. Johnston to William T. Sherman at Bennett Place, Durham, North Carolina, few days later ended the Confederate resistance and the war was de facto over.

Path to Lee’s Surrender

Lee was forced to abandon Petersburg and Richmond after the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Five Forks on April 1, 1865, because he had been cut off from the last supply line. He retreated to Amelia Court House but he found no provisions when he reached the city on April 4. Meanwhile, Lee learned that his path to Danville was blocked by the Union forces. This forced him to change his plan which foresaw withdrawal to South Carolina via Danville. Lee decided to move westwards to Lynchburg via Farmville but he had lost about 7,000 men at Sayler’s Creek on April 6. He reached Appomattox Courthouse on April 8, however, he soon realized that he was surrounded by the Union forces on three sides and that the situation was hopeless.

Lee’s Request for Meeting with Grant to Discuss the Terms of Surrender

Grant received Lee’s letter requesting a meeting to discuss the terms of surrender early in the morning of April 9. Grant replied that he would meet him at the place of his choice. When he received Grant’s reply, Lee sent his aide de camp, Charles Marshall to find a suitable location. Marshall had chosen the home of Wilmer McLean in the village of Appomattox Courthouse and notified Lee about the location.

Meeting between Lee and Grant at the McLean House

Lee arrived to the McLean house in a brand new uniform about 1:00 a.m., while Grant got there about half an hour later wearing a mud spattered private soldier uniform (only his shoulder straps revealed his rank). In contrary to Lee with a new sword hanging at his side, Grant wore no side arms. After greeting each other, the two generals briefly talked about their encounter during the Mexican-American War two decades earlier when Lee finally got to the point of the meeting and asked Grant about the terms of surrender. Grant later admitted that he had found it hard to open the question of surrender.

Terms of the Surrender

The terms of the surrender were simple and very generous. All Lee’s men and officers were to be paroled and to return home. Officers were allowed to keep their side arms, private horses and personal effects, while the arms, munition and supplies were to be handed over to the officers appointed by Grant. Lee once again took the initiative and asked Grant to put the terms on paper. When Lee read the terms, he asked Grant if his private soldiers were allowed to take horses and explained that they would need them for farming when returning home. Grant replied that he would not change the terms of surrender, however, he promised to instruct his officers to allow any Confederate soldier claiming a horse or mule to take the animal. Lee expressed gratitude to Grant stressing the positive effects of such concession and when he mentioned being without rations for several days, Grant immediately offered 25,000 rations.

Outcome of the Meeting at McLean House

Lee signed the surrender document about 4:00 p.m., shook hands with Grant and left the house. Grant and his officers followed him outside and took off their hats. Lee raised his hat in response and rode off to his camp about half a mile away announcing that he had surrendered.